Connected Parenting Workshop

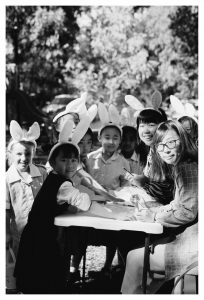

Lael Stone – Connected Parenting Workshop presented by Tintern Grammar and The Resilience Project

In early May, Middle School and Senior College parents gathered in the CM Wood Centre to learn more about parenting and how they can better connect with their teens by finding new ways of supporting family emotional stability in the home.

For almost two decades, Lael Stone has worked with families to improve relationships and manage trauma. Drawing from her own experiences of parenting three teenage children, her work has culminated in her development of a range of well-being programs implemented in many secondary schools. As a part of this work, Lael identified that many mainstream educational settings were failing to address a substantive area of personal development. This led to her co-founding an innovative school in the hinterland of Geelong, prioritising the development of each student’s emotional intelligence alongside academic learning. Lael came to Tintern as part of The Resilience Project’s ongoing commitment to student and community wellbeing. Photographs of her presentation can be found on The Resilience Project Tintern Parent Portal Page, which also has a link to the resources available from The Resilience Project@Home, where parents can find a range of strategies on how to continue using the rhetoric of Gratitude, Empathy, Mindfulness and Emotional Literacy which are applied in our senior and middle school classes, in your own home.

On May 4, Lael began her presentation with the neuro-behavioural science of adolescence, explaining neurological changes that stereotypically cause adolescent mood swings. She emphasised to parents that the prefrontal cortex – the risk-mitigating part of the brain, does not fully develop until a person’s late 20s, making it quite understandable that teens are unable to foresee consequences. It would be like asking the same adolescent to clean and jerk a weightlifting bar with 100kg of weights in the gym. It’s physiologically impossible (for most people). This upside of this lack of inhibition, however, is young people are open to a world of opportunities that are presented to them, broadening their curiosities and facilitating an unbridled passion about the world. This is the precursory step for them to finding their voice and place in the world. Think of the times your teen comes home fixated on an issue that has arisen, and they cannot talk about anything else. These are moments of personal and neurological growth. It is important to let your teen know you hear them and value their point of view, even if you don’t agree with it.

It is helpful that the prefrontal cortex is most active during the day when your child is exposed to stimulation and ideas at school and with their friends. The amygdala, on the flipside, at the centre of our brain, is where our emotions are assigned meaning and you guessed it, this becomes more active at night. Habitually, this is when adolescents are more emotionally vulnerable, but of course, it is also when they can be very active on social networks. It is in these late hours of the night that the rollercoaster of emotions leaves the terminus, and amongst other things, sleeplessness and angst can set in. Having said this, the amygdala certainly likes to meddle in our diurnal experiences, which is why we have the full gamete of teen emotions available at any given moment of the day.

Lael has coined some “family-friendly” terms that she encourages parents and carers to use when they see shifts in mood in their teens. The more emotionally regulated person she termed as someone who is “in-balance”, whereas the person experiencing a wider, often more volatile range of moods is referred to as someone who is “out-of-balance”.

The in-balance adult/adolescent/child is adaptable, responds to instructions/requests with agreeance or even offers to help, talks respectfully to other members of the household including pets and siblings, and is more or less adaptable to any challenge and discomfort that may arise. The out-of-balance adult/adolescent/child is more reactive, perhaps showing up as defensive, angry or sullen behaviours, or manifesting as a barrage of emotions when you instruct/request assistance. Dismissive and aggressive to other members of the household can be the default response even without realising they are doing it.

Although people of any age can feel out-of-balance, adults usually have a wider range of coping strategies to help them navigate this unbalance. Things like exercise, meditation, chatting with a friend on the phone, listening to music, working out, eating chocolate, drinking wine, online shopping (well, maybe not those last three) are all ways we may mitigate feelings of overwhelm. Teens are yet to discover these strategies, and so are more readily primed for these outbursts, often with a hair trigger. As parents, it is our job to emotionally hold our teens (and children and each other, for that matter), to help them feel safe as they ride these emotions out.

At this point, many parents may feel the urge to come to the rescue. Extending the rollercoaster metaphor used earlier, parents usher their teen from the carriage and then step up to ride the rollercoaster for them. Although this does (usually) fix the problem easily and quickly, it does not help teens in the long term. Experiencing unpleasant emotions like discomfort and uncertainty are all very important parts of emotional development. They facilitate emotional intelligence and teach them strategies to manage disappointment, failure and loss. With exposure to these feelings comes improved emotional awareness, and even more importantly, their articulation fosters emotional literacy and the ability to experience empathy for others. To problem solve and “fix” every hurdle our children/adolescents face, means they will never learn to persist in the face of adversity. Although it can be a very difficult step to take, parents must work on being ‘okay’ with their child becoming increasingly exposed to disappointment, failure and discomfort.

So, how do we better provide the safety net for our children while allowing them to develop into emotionally intelligent adults and still have recognisable boundaries? Lael has found adolescents respond well to the following strategies:

1. If the issue is between you and your teen, be sure you have worked through your own feelings about the trigger before you deal with your child’s emotions and behaviours. You may perceive they have betrayed your trust or disappointed you. Other common feelings may include anger and frustration. If you can’t manage these feelings in the moment and remain calm, tell the child to go away and have some space from you, and come back to discussing what has happened later (the next morning or in a few hours).

2. Be prepared to own whatever part you have played in creating this situation. This may be things like you were too busy to help them when they needed you, or perhaps you were too enthusiastic, pushing your own agenda/needs, rather than focussing on the child’s own needs/desires? Think about these agendas – as they may not be obvious at first, but they are usually hiding in there, somewhere.

3. Begin with restorative practices – by articulating the above points in a calm manner. Owning your part in the frustration/hurt etc. shows them you also vulnerable and engaged in finding a solution. They will need to hear this to feel safe.

4. Allow them the same opportunity to voice their feelings. It is okay to have boundaries and enforce them, but we must acknowledge the feelings these boundaries create, to be able to move forward. 5. When your teen speaks, respond in ways that facilitate their conversation. Use questions/comments that invite them to continue like “Tell me all about it…” and “What happened then?” or “That must have been hard?”

5. When your teen speaks, respond in ways that facilitate their conversation. Use questions/comments that invite them to continue like “Tell me all about it…” and “What happened then?” or “That must have been hard?”

6. Be sure to spend time with your teen outside of these moments, doing something they value. e.g. let them give you a facial, do your make up, wash their car with them, lie on the grass and look at the stars/clouds. These moments provide a platform where extremely meaningful conversations can begin.

7. Recognise when you have done a good job and own this.

Space is the most important response if these strategies lead to an escalation of emotion in either adults or teens. When you acknowledge space is needed, it gives you time to think through the emotions before they are talked about, and come back to the issue at another time. If your teen comes to you ready to speak, acknowledge their initiative and make sure you are ready to discuss it. Over time and with practice, teens will better learn to navigate triggers and even become a role model of how other children (and adults) can manage these challenging situations. This surely has to be something every parent hopes will happen for their children, and inevitably leads to a happier, more stable home environment.

Rebecca Infanti

The Resilience Project Coordinator